The vast majority of cases in which twin births among humans occur involve either the simultaneous fertilization of two oocytes (or human egg cells), or when the cells from a single fertilized egg split to form two fetuses. These events determine how identical the resulting twin babies could be. In the latter case, they will be 100% genetically similar, and in the former, this similarity will fall to about 50%.

However, doctors have recently identified a third mechanism that produces a twin birth.

This process begins when an egg cell is fertilized by two spermatocytes (or sperm cells). This occurrence, which is rare enough on its own, usually results in a single fused zygote (a cell type into which a fertilized egg cell transforms) with three sets of chromosomes rather than the usual two.

The fetus that would develop from such a cell would be inviable, and any resulting pregnancy would not be likely to progress beyond an early miscarriage.

In rare cases, two sperm cells fertilize a single egg cell. (Source: Queensland University of Technology)

The Third Way to Twins

However, it appears that there are a few cases in which another path is taken. In these cases, the initial zygotic cells manage to ‘sort’ their chromosomes so that one half of this have two sets of chromosomes each. These cells arrange themselves into two fetuses during the course of the pregnancy. In other words, the tri-chromosomal zygote results in twins.

This outcome is even scarcer than a double-fertilized egg, and results in what are known as sesquizygotic twins.

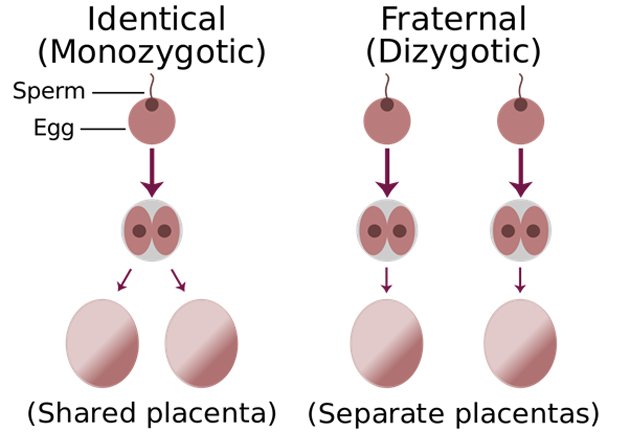

Sesquizygotic twins can mimic a typical pregnancy that involves identical twins (or monozygotic twins), as they also share the same placenta and arrange their amniotic fluid in a specific way. Dizygotic twins, on the other hand, can exhibit two placentas and two amniotic sacs.

Sesquizygotic twins may diverge in terms of biological sex, whereas monozygotic twins cannot. It was this attribute led a fetal medicine team at the Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital, Brisbane, Australia, in 2014, to successfully identify a case of sesquizygotic twins. This resulted from a routine ultrasound scan at the 6th week of the twins’ mother’s pregnancy.

Monozygotism leads to a shared placenta, whereas dizygotism does not. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The resulting children – a girl and a boy – are now healthy four-year-olds. They are only the second instance of sesquizygotic twins recorded in medical literature so far this century. The first case was verified and reported in the US in 2007.

This later-manifestation of a sesquizygotic pregnancy has also been written up as a case report. It has been published in the New England Journal of Medicine by Professor Nicholas Fisk (who led the Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital team that cared for the mother in 2014, and also holds a Deputy Vice-Chancellorship at the University of New South Wales), Dr. Michael Gabbett (a clinical geneticist at Queensland University of Technology) and their colleagues.

These authors reported that a genetic analysis of the two babies showed that, although they shared 100% of their maternal DNA, they had only 78% of their paternal DNA in common.

The fetal genetics researchers also went through a database of genomes previously gathered from 968 cases of dizygotic twins, but did not find evidence of sesquizygotism in even one of them. This was done through the technique of pangenome single-nucleotide polymorphism genotyping. The authors examined pre-existing records of twin births, which also failed to result in a hint of this kind of twin birth.

Could Another Case of Sesquizygotic Twins be Found?

Accordingly, Dr. Gabbett and Professor Fisk do not particularly advise other fetal medicine groups to do the same in order to identify any possibly overlooked case of sesquizygotism from the past. The odds of one turning up is so small that, as the researchers have indicated, there is essentially no point in looking. Similarly, they do not encourage any groups to conduct genetic screening on twin births with the aim of finding these ultra-rare cases.

All in all, identifying a phenomenon as rare as sesquizygotic twins may seem like an attractive route to scientific fame and recognition. However, as with many similar academic pursuits, the odds are not in any researcher’s favor.

Top Image: The sesquizygotic twins were discovered through an ultrasound image much like this, but with crucial differences. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

No comment