It’s suggested that Hurricane Harvey is the largest flooding rainstorm to ever hit the United States. The intense rainfall and speed with which the storm intensified caused widespread devastation and a “1,000 year flood” that will take years for the affected communities to recover from.

Now, hot on the heels of Hurricane Harvey, Hurricane Irma is coming steaming across the Atlantic Ocean. At the moment, it looks as though Irma is heading for a collision course with Florida over the weekend. Irma has been categorized as a Category 5 storm, the most severe possible classification which has the potential to cause catastrophic damage.

The European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts is widely accepted to have the most accurate hurricane forecasting model. They have suggested 52 possible paths for Hurricane Irma, with all of these currently passing through Florida, or near the coast. With the current public advisory notice published by the National Hurricane Center suggesting that hurricane force winds are extending 120km (75 miles) out from the center of the hurricane, and tropical-storm force winds extending to 295km (185 miles) residents have been advised to evacuate early. At the time of that report (2.00AM EDT September 8) the maximum sustained winds within the hurricane were found to be 260km/h (160mph).

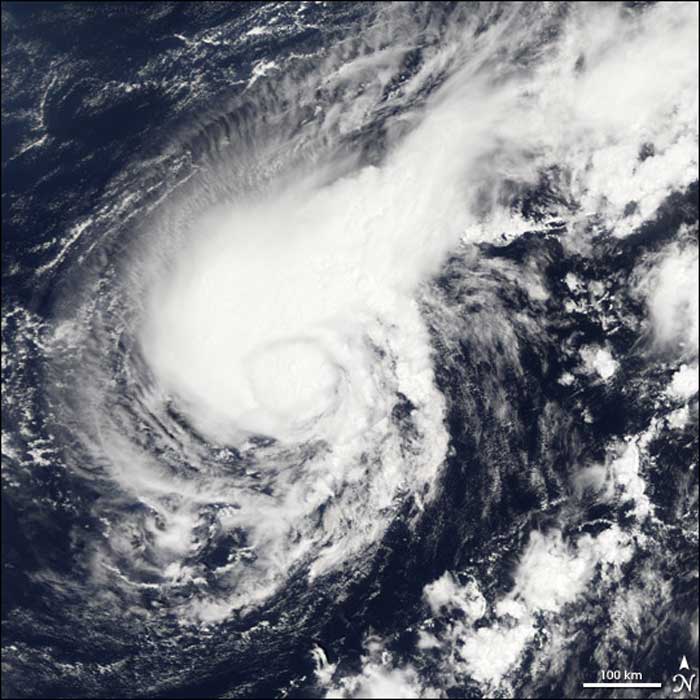

Tropical Storm Harvey (NASA image created by Jesse Allen, Earth Observatory, using data obtained from the MODIS Rapid Response team.)

Are hurricanes getting stronger?

With two Category 5 hurricanes within a matter of weeks, many people will be wondering whether or not this is going to be a new normal?

The answer, is possibly, yes.

Climate scientists now agree that while it’s impossible to say that climate change alone caused Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, it certainly will have made them much stronger.

Anders Levermann, a climate scientist based at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, said: “Unfortunately, the physicality is very clear: Hurricanes get their destructive energy from the warmth of the ocean, and the region’s water temperatures are super elevated.”

He went on to say that climate change can “badly exacerbate” the force of a hurricane even if it’s not the initial cause. Hurricane expert Julian Heming, based at the UK’s Met Office agrees that the intensity of Irma is most certainly down to higher than average temperatures of the sea surface for this time of year, which is “fueling Hurricane Irma, giving additional energy and moisture.” He went on to say that: “A hurricane of this magnitude will have impacts extending far from its center, so it’s important for residents not to focus on the exact forecast track but to consider the system as a whole. Intense rainfall, flash floods, extreme winds and a life-threatening storm surge will severely affect communities over a wide area.”

Will there be as many hurricanes?

Other climate scientists also suggest that there could be a trade-off, with some suggesting that whilst the hurricanes that form do seem to be growing in intensity, we may find that they also form less often.

James Elsner, a climate scientist at Florida State Univeristy, says that: “If you look at frequency and intensity together, it appears that it’s really the efficiency of intensity that matches the global-warming signal the best. The strongest get stronger, but at the expense of the number of storms.”

Elsner and his colleague Nam-Young Kang published a review in Nature Climate Change titled ‘Trade-off between intensity and frequency of global tropical cyclones’ which found a trend over the last 30 years towards more powerful, but less frequent storms.

4th Reconnaissance Marines support rescue efforts in wake of Hurricane Harvey. (navylive.dodlive.mil)

That suggestion might seem ironic given the short amount of time between Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, and other climate scientists are certainly not convinced yet. Basically, much more data is required before this theory is widely accepted. Another issue is that global hurricane records have not been recorded for long enough to give a true indication of whether or not they are truly becoming less frequent but more intense.

Thomas Knutson is co-author of the US Climate Science Special Report. This report is a government review of climate science, due out later this year. Knutson say that: “One of the most robust results we see from model simulations is that hurricanes have higher rainfall rates. We interpret that as happening because, in a warming climate, the atmosphere is holding more water in general—and a hurricane brings air into its center and wrings water out of it as precipitation.”

So, whilst climate scientists are confident that climate change is affecting our coral reefs and sea levels, the impact on hurricane formation is currently not as clear-cut. Despite that, Katharine Hayhoe, also a co-author of the Climate Science Special Report says that: “Just about everyone agrees that the amount of rainfall associated with storms and hurricanes is increasing—and the risk of storm surge and coastal flooding is worsening, as well, because of sea-level rise.”

Whilst none of this will be of much comfort to those affected by these deadly hurricanes, it certainly suggests that governments, communities and individuals need to consider adapting their infrastructure and responses for the future, in order to better be able to cope when hurricanes hit.

Top image: Soldiers with the Texas Army National Guard move through flooded Houston streets as floodwaters from Hurricane Harvey continue to rise, Monday, August 28, 2017. More than 12,000 members of the Texas National Guard have been called out to support local authorities in response to the storm. (U.S. Army photo by 1st Lt. Zachary West) (Public Domain)

No comment