The Montreal Protocol was brought in thirty years ago, in an attempt to reduce and eventually remove the sale of chemicals which had been implicated in the destruction of the ozone layer. Whilst the protocol has certainly helped reduce emissions of these dangerous chemicals, new research has now shed light on the fact that there is another risk to the ozone layer, from substances which are not covered by the Montreal Protocol.

Unregulated chemicals

The new study, titled ‘A growing threat to the ozone layer from short-lived anthropogenic chlorocarbons’ was published in the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics on October 12. In it, lead author David Oram, from the University of East Anglia in the UK, details how he and his team collected air samples from a range of sites around the South China Sea from 2012 to 2014 before taking the samples back to laboratories in the UK for analysis.

The research team concentrated on this area due to the fact that emissions from around China are particularly dangerous to the ozone layer because they are quickly carried to the tropics, from where they are swept up and into the ozone layer.

The main chemicals identified were dichloromethane and 1,2-dichloroethane. Dichloromethane is used for a variety of applications including stripping paint and pharmaceutical production. Dichloroethane is used to make PVC and is already indicated as a substance which can deplete ozone. As a highly toxic chemical that is expensive to produce, Oram expressed surprise that they found so much in the atmosphere, saying: “One would expect that care would be taken not to release [dichloroethane] into the atmosphere.”

The source of the chemicals was also considered, with Oram saying: "We expected that the new emissions could be coming from the developing world, where industrialisation has been increasing rapidly. Our estimates suggest that China may be responsible for around 50-60% of current global emissions [of dichloromethane], with other Asian countries, including India, likely to be significant emitters as well."

Data was also collected using passenger aircraft flying over Southeast Asia, in an attempt to find out whether the chemicals were present in significant amounts at altitude. Unfortunately, the data collected did indeed show that these chemicals were spreading, as explained by Oram: "We found that elevated concentrations of these same chemicals were present at altitudes of 12 km over tropical regions, many thousands of kilometres away from their likely source, and in a region where air is known to be transferred into the stratosphere."

Taking swift action

Whilst the Montreal Protocol has certainly been a success in reducing emissions of chemicals that can harm the ozone layer. Unfortunately though, in the years since the protocol came into force, the rise in use of other harmful chemicals not covered by the protocol is creating new threats to the ozone layer.

Oram said that not taking action to reduce these emissions could easily impair recovery of the ozone layer: "At the moment an average date for ozone recovery could be about 2050 but there are studies that say this could be delayed by 20-30 years depending on future emissions of things like dichloromethane. We are highlighting a gap in the Montreal Protocol that may need to be addressed in the future, particularly if atmospheric concentrations [of these substances] continue to rise.”

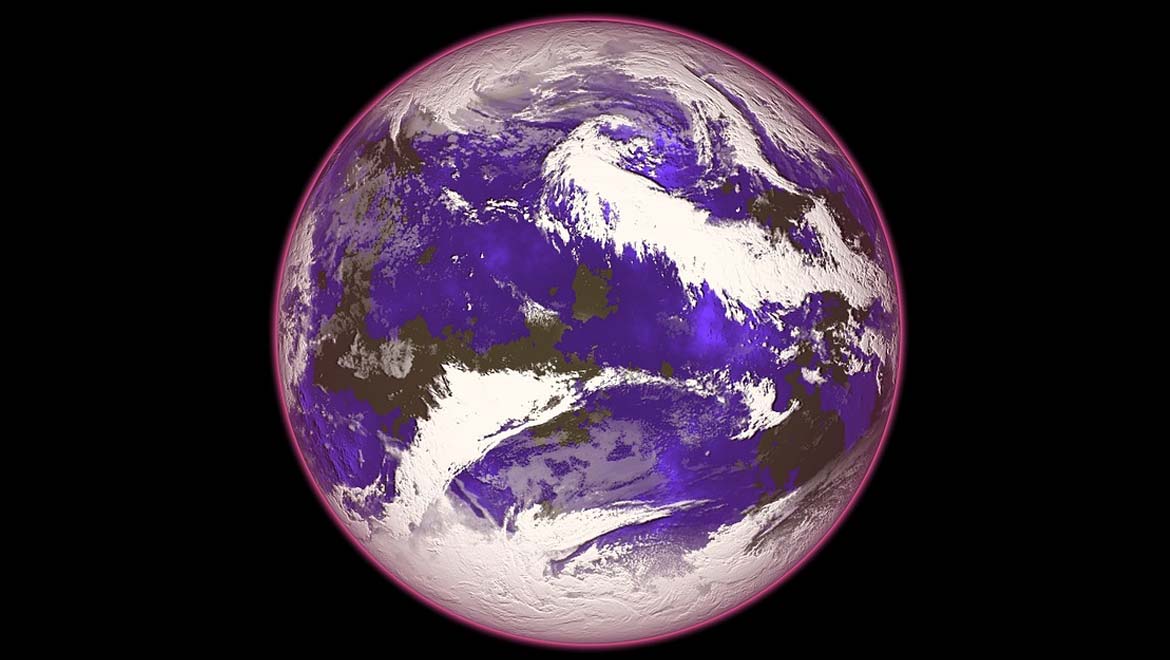

Top image:Ozone Layer. (Public Domain)

No comment