Some researchers have concluded that air pollution is associated with a reduced life quality in human beings. This even extends to humans in utero, as recent findings have indicated. These studies have found some evidence that pollutant particles, which are inhaled by pregnant women, can have an effect on resulting fetal development. In addition, it has been reported that these effects may extend beyond birth and, at least, into the first year of life.

However, there has been little research on why exactly this may be; for example, it was not clear if this link was caused by air pollutants passing into the placenta via the pregnant woman’s lungs.

Evidence of Air Pollutants in Placenta

Two researchers from the Queen Mary University in London decided to answer this impending question in a study. The scientists, Dr. Norrice Liu, and Dr. Lisa Miyashita obtained permission to take placental samples from five women scheduled for delivery via a cesarean section at the Royal Hospital in London.

Liu and Miyashita hypothesized that they could find evidence of placental contamination with air pollution by analyzing the macrophages found in these samples.

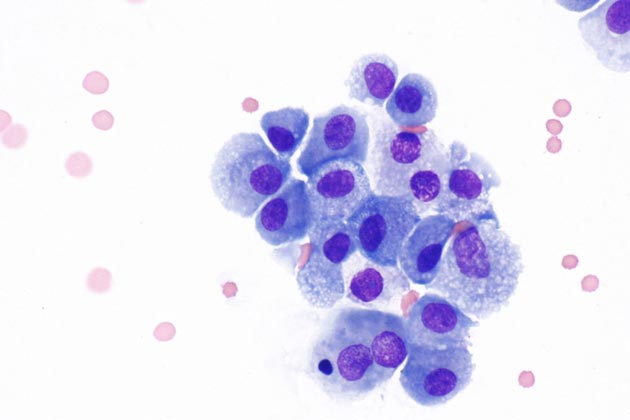

Macrophages (one of which in this image has engulfed a foreign body (blue dot)) are found in multiple tissues. (Source: Librepath/Wikimedia Commons)

Macrophages are a type of cell found in many different tissue types, including the placenta. These cells function to isolate potentially harmful foreign particles from their surroundings by engulfing them. The macrophages then store these bodies in specific vesicles, until they break down or can somehow be transported out of the body.

Therefore, placental macrophages could contain the inert pollutant particles (that the team was looking for). These particles are tiny grains of carbon and other, potentially more acutely harmful substances, released into the air following fossil fuel combustion.

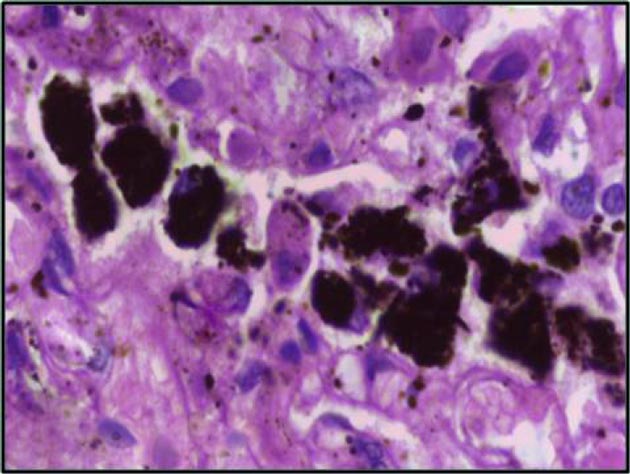

Macrophages from lung samples have been found to have encountered and engulfed carbonaceous particles. (Source: Department of Pathology, Calicut Medical College, India/Wikimedia Commons)

Liu and Miyashita pooled the macrophages from the five placentas, purified their placental macrophages and assessed them under high-powered microscopy. As a result, the two researchers found that a total of 1.7% of their total cell population exhibited “black dots” in their vesicles. The microscopic images indicated that these dots could cover an area of 5mm2 if they were all grouped together.

The researchers then re-assessed the cells from 40% of the donors, this time using electron microscopy. Again, they identified particles believed to be carbonaceous structures.

Therefore, this study may provide the first concrete evidence that air pollutants, taken in through the lungs, can end up in the placenta.

Limitations of the Study

The researchers were not able to conclude that these particles could be present in, or otherwise affect, the fetus in question, based on these findings. In addition, the ‘black dots’ described in this study need to be analyzed in finer detail in order to confirm their identity as the types of carbon compound found in air pollution. Also, the researchers did not report data on the demographics of the placental donors that may have affected these results. These may include the geographical areas or where they spent significant amounts of time.

There is an obvious confounder in the design of this study, and that is whether or not the women involved were smokers. Such a lifestyle choice is an unavoidable source of respiratory contaminants that can persist in the body, even if the pregnant woman quits for the nine month-gestation.

However, Liu and Miyashita reported that none of the five women who agreed to take part in their research were smokers. This factor may exclude other potential participants from future studies along these lines.

Future of Research

The researchers asserted that their findings could have some merit in respiratory health medicine. Dr. Liu notes that the particles, should they be proven to be airborne pollutants, may not necessarily need to pass into a growing fetus to affect development.

The study may also give weight to previous work that has drawn an association between pregnancies that progress in more polluted areas (e.g., cities) and issues such as reduced birth weights, premature births, and developmental issues.

This piece of research was presented at the recent European Respiratory Society (ERS) International Congress, and it certainly warrants the need for further studies on the subject.

This avenue of research could elicit a convincing mechanism for the effects of air pollution in utero. First, however, the initial trial may have to be validated and replicated with larger participant groups and sample sizes. This may be followed by comparative studies between, for example, women living in more urbanized (and mechanized) environments, and those who do not. Finally, the eventual results may one day inform air quality guidelines, and possibly even lead to their re-evaluation.

Summary

A pilot study conducted at Queen Mary University in London may have provided preliminary evidence that carbon-based air pollutants are found in the placentas of pregnant women. These findings require confirmation at this point; however, it may still be a worrying indication of the effects of reduced air quality on fetal development in the area of respiratory medicine.

Top Image: Air pollution has been strongly linked to negative health outcomes such as issues in normal fetal development. (Source: Public Domain)

References

First evidence that soot from polluted air is reaching placenta, European Lung Foundation, http://www.europeanlung.org/en/news-and-events/media-centre/press-releases/first-evidence-that-soot-from-polluted-air-is-reaching-placenta/ , (accessed 19 September 2018)

N. Liu, et al. (2018) Late Breaking Abstract - Do inhaled carbonaceous particles translocate from the lung to the placenta? European Respiratory Society International Congress.

Z. Maghbooli, et al. (2018) Air pollution during pregnancy and placental adaptation in the levels of global DNA methylation. PLoS One. 13:(7). pp. e0199772.

O. Laurent, et al. (2016) Low birth weight and air pollution in California: Which sources and components drive the risk? Environ Int. 92-93: pp.471-477.

No comment