As summer starts in the Northern Hemisphere, many of us are reminded of the dangers that heatwaves can bring. Weather warnings for excessive heat have just been issued for Phoenix, Arizona, with temperatures due to reach a sweltering 119 degrees Fahrenheit (48.3 degrees Celsius). This heat can pose a massive threat to our environment with dangers of wildfire and droughts, but it can also play havoc with our bodies.

These heatwaves often bring with them a serious risk of heat-related illnesses, including heatstroke. If our core body temperature rises above 104 degrees Fahrenheit (40 degrees Celsius) our cells literally begin to break down. It might seem surprising to discover that heatwaves are responsible for more deaths in the US than any other extreme weather-related events, including tornadoes.

Climate change and a hotter Earth

Currently, around 30 percent of our world population are exposed to levels of heat which can pose a risk of death, for 20 days or more per year. An unfortunate effect of climate change and our warming globe is that this percentage is only going to increase in years to come.

Heatwaves are already surprisingly common around the world, and often unfortunately result in a significant number of deaths. In Europe, a heatwave in 2003 killed around 70,000 people, with a heatwave across Western Russia in 2010 causing the deaths of 10,000 people. Currently, India and Pakistan are experiencing a heatwave with temperatures reaching a staggering 128 degrees Fahrenheit (53.5 degrees Celsius).

Tracking heat-related deaths

A team led by Camilo Mora from the University of Hawaii set about trying to discover more about these extreme weather events. The research, titled ‘Global risk of deadly heat’ was published Monday 19 June in Nature Climate Change.

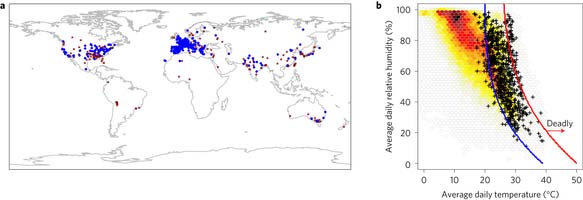

Mora and his team completed a literature review of papers relating to heat-related deaths across 36 different countries over the past four decades. They identified the threshold between lethal and non-lethal events and observed the differences between temperature and humidity around this threshold. They discovered that the threshold varies from area to area, with a vital factor being the levels of humidity combined with heat. A temperature of just 86 degrees Fahrenheit (30 degrees Celsius) can be deadly if it is also combined with a very high level of humidity.

Geographical distribution of recent lethal heat events and their climatic conditions. (Nature)

The scientists conducting this study also looked at identifying when and where the lethal heatwaves occurred, as well as creating a climate model to predict the frequency of these events in the future. Iain Caldwell, an author on the paper and also based at the University of Hawaii, said “we formed climate models of three possible future climate scenarios: one with no change in carbon emissions, one with moderate mitigation, and one with strong mitigation. We found that there already seems to be an increase in the number of deadly days since the past and that those deadly conditions could increase substantially in the future, particularly if we do nothing to reduce our impacts on climate change.”

From their models, the authors suggest that by 2100, the percentage of global population likely to be exposed to lethal heat events could rise to 74 percent if greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated. If however, greenhouse gases are reduced significantly, the figure falls to 48 percent.

This means that even if we do drastically reduce our global emissions, by the end of the century, just under one in two people will most likely be experiencing the effects of these deadly heatwaves.

Lead author Camilo Mora, summed things up by saying “our attitude towards the environment has been so reckless that we are running out of good choices for the future.” Those of us who have experienced the adverse effects of these extreme combinations of heat and humidity know all too well that this is a challenging legacy to leave future generations with.

Top image: Hot day ahead. Mamallapuram, India (CC BY-SA 2.0)

No comment