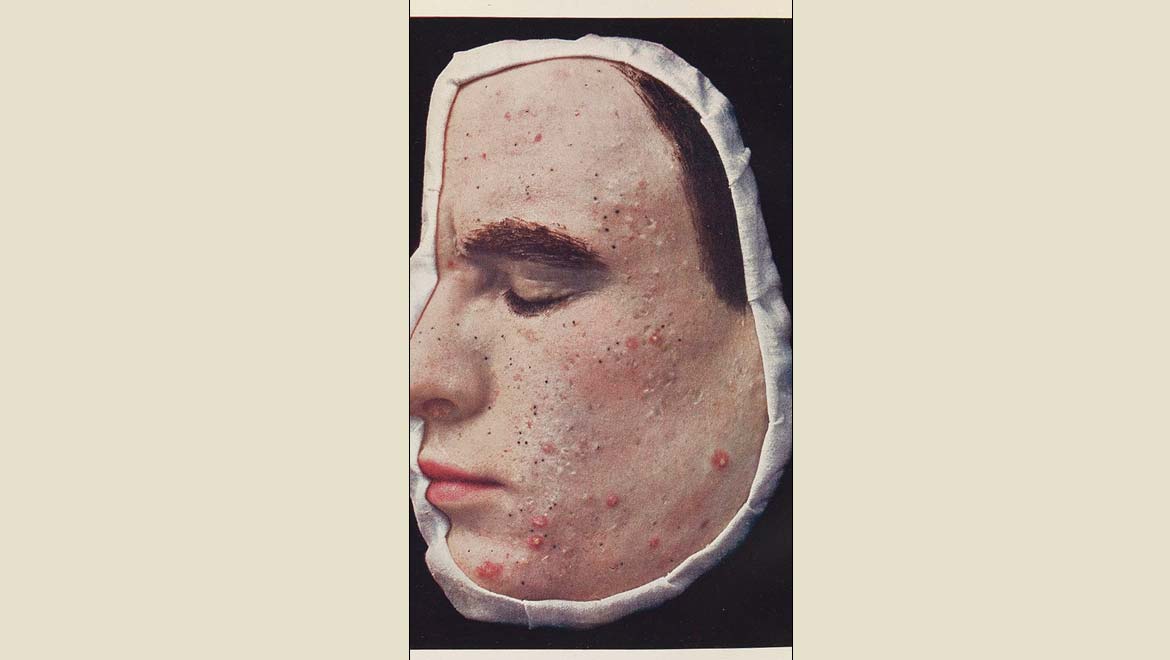

Acne is a condition in which small, red, pink or purplish lesions appear on the skin of patients. It can be restricted to the face, or appear elsewhere on the body. This condition may be chronic (or a long-term, persistent problem) in some individuals. However, in other cases, it is thought to be related to other variables, which can range from hormonal imbalances to emotional stress. Acne can often result in reduced life quality due to the impact on self-perception, confidence and comfort experienced by many patients.

The Acne-Causing Bacterium

This condition is associated with the bacterial species, Propionibacterium acnes. It has been found to live on human skin and be extremely abundant across communities. The prevailing theory of acne is that P. acnes promotes the formation of acne lesions by enhancing inflammation in the skin affected. However, this model of acne development and progression has come up against problems in recent years. This is due to findings that P. acnes can be present in the skin without causing acne lesions of any kinds.

These findings have been backed up by other recent studies of the genomic-analysis kind. They have found that P. acnes strains can differ significantly in their ability to cause acne. This has led to a new theory of acne: there are ‘good’ (or healthy) P. acnes, as well as ‘bad’ strains of the same bacterium. Therefore, the presence of one rather than another may influence the risk of acne development.

If this theory could be proven, it could lead to a profound reassessment of the current treatment practices for this condition, particularly in severe, treatment-resistant cases.

Unfortunately, there have been few options to date with which to test this theory. Ideally, scientists should start with an animal trial of some appropriate kind. However, ‘acne models’ in laboratory animals are harder to elicit compared to those for many conditions. This is because the skin of rodents, for example, is of a markedly different make-up compared to human skin. Therefore, their exposure to P. acnes just does not result in the lesions seen in people. Therefore, it is largely impossible to apply new candidate treatments or theories to them in the dermatology lab.

This was the case – until now.

A team of scientists from the University of California’s (San Diego) School of Medicine, the University of California (Los Angeles) and Cedars-Sinai Hospital have developed a more effective model of human skin in mice.

This was done by preparing a batch of synthetic sebum, which was then integrated into the skin of these test animals so that it mimicked human skin much more closely.

Sebum is a fat-rich substance secreted by human skin as a natural form of protection against pathogens. Unfortunately, P. acnes appears to thrive on it. This interaction is thought to drive the increased risk of acne during puberty, as sebum secretion is often elevated in teenagers as they go through this phase of life.

The UCLA/UCSD/Cedars-Sinai team made their artificial sebum out of squalene (the precursor to sterols, which then form the cholesterol-molecules often found in skin) fatty acids, triglycerides, and wax. They applied this formula to the mice daily, and also inoculated them with either ‘healthy’ or ‘acne-linked’ P. acnes strains.

Making Mouse-Skin More Human -- For Science!

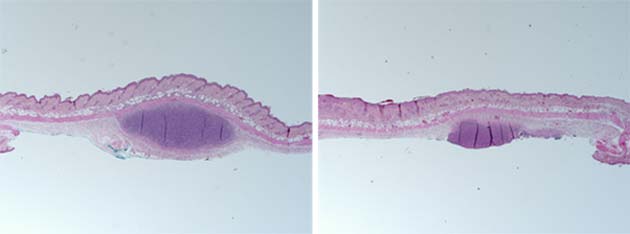

The researchers reported that the latter kind of P. acnes was associated with acne-like lesions in the mice. In addition, these strains were able to survive for weeks in the presence of the fake sebum, whereas the murine skin immune system would get rid of them under normal circumstances. In addition, these bacteria were also associated with increased levels of inflammatory cytokines in the animals.

By comparison, the ‘healthy’ P. acnes strains were not associated with these changes and did not survive longer than three days in the animals’ skin.

These mice were all engineered to be genetically identical and received the same ‘sebum’ formulation throughout the experiment. Therefore, the only variable that was altered was the type of P. acnes to which the animals were exposed.’

A microscopic view of mouse-skin samples treated with synthetic human sebum and with either acne-associated (left) or health-associated P. acnes (right). (Source: UC San Diego Health)

Therefore, the team now conclude that this is the first piece of empirical evidence that shows how different strains of P. acnes are associated with differing effects on the risk of acne development.

This research has been published in a March 2019 issue of the journal, JCI Insight.

Furthermore, other groups have identified the bacterial genes that appear to determine the same. Therefore, these scientists now believe that new therapies that specifically target these genes (e.g., vaccines) could be the next, and possibly most effective, method of acne treatment.

On the other hand, this animal model focuses on one factor of acne development, whereas there are many others that are widely acknowledged among the dermatology research community. They include differential skin-lipid profiles, inflammation, other skin anomalies, increased androgen levels, and even genetic predisposition. Then again, new and more refined treatments for the condition would also be potentially welcome.

Currently, severe or chronic acne is often thought to require retinoid (vitamin A derivatives) therapy. This line of treatment has been associated with serious side-effects, which may include the increased risk of depression, psychosis, bipolar disorder and defects at birth, in the event of a pregnancy.

In addition, antibiotics have also been recommended to treat acne in the past. This treatment may prove ineffective, and also increases the risk of antibiotic resistance in P. acnes and other bacteria.

Therefore, the novel option implied by the ‘bacterial dichotomy’ theory of acne may be a positive development for the future of skincare.

Top Image: Acne is characterized by the appearance of often numerous small inflammatory lesions on the skin. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

No comment