Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a prevalent form of neurodegeneration that affects cognition and recall, in advanced ages. The condition is associated with estimates of billions of dollars’ worth of healthcare burden in the US alone. On the other hand, AD may share these costs with similar forms of dementia like progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP).

Alzheimer's is currently thought to be associated with pathological proteins within and around important brain cells. This is due to abnormally high expression rates and patterns for these proteins, in patients affected by AD, and it may have a genetic component.

Theories about Alzheimer’s Onset & Progression

Now, there are other prominent, competing theories for AD onset and progression. One of these, i.e., a 'viral' theory, is enjoying a rapid renaissance these days.

This theory states that AD is associated with viral infections that are caught in childhood. They then remain dormant in the body until they can manifest again in the form of accelerated neurodegeneration. The viruses may do this by activating a panel of human transcription factors (regulatory proteins that function to control gene expression), which, in turn, activate a cascade of other regulatory or signaling proteins. These ‘signals’ expedite the clinical characteristics of Alzheimer's disease.

On the other hand, there has been little enough evidence to support this theory throughout the history of the Alzheimer's, since its original proposal in the mid-1950s.

For example, some researchers have asserted that chronic infection with the herpes simplex virus can drive AD slowly over time. This could be in the same way that other herpes viruses contribute to peripheral neuralgia, following an initial case of a cold sore, for instance.

However, these claims have been backed up with minimal amounts of correlation and defined physiological mechanisms.

It now appears that the viral model of Alzheimer's disease is back, albeit with different human Herpesviridae viruses this time. They are human herpesvirus 6A (HHV-6A) and herpesvirus 7 (HHV-7). Both of these are popularly associated with the minor disease, roseola, which affects about 90% of all children in the US. This condition, marked by an acute fever followed by a rash, is usually mild and recedes without complications for the remainder of life.

But some researchers now suggest that HHV-6A and HHV-7, in fact, remain dormant, until they can contribute to a case of AD later in life.

Study Confirming Association between AD and Herpes Virus

This indication has been corroborated by a recent paper in the Neuron journal. The research, led by John Dudley of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the ASU-Banner Neurodegenerative Disease Research Center at Arizona State University (Tempe), claims to have found that these viruses were significantly abundant in post-mortem brains from Alzheimer's patients compared to matched controls.

The team also conducted a multi-omics analysis (i.e., RNA, DNA, proteomic, transcriptomic and clinical parameters) of this brain tissue. This allowed them to conclude the presence of HHV-6A and HHV-7, and certain regulatory proteins had statistically significant relationships in AD cases.

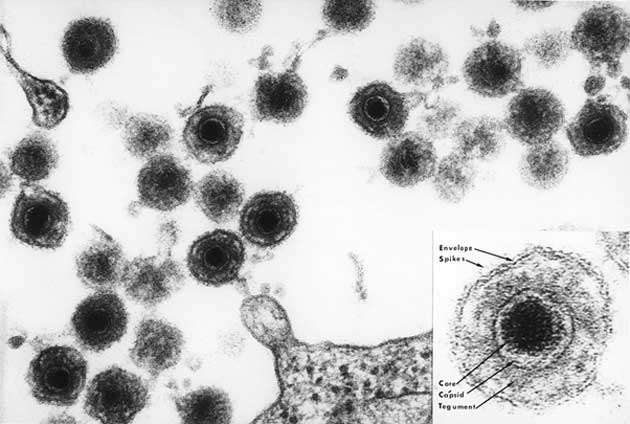

An electron microscopy-generated image of HHV-6. (Source: Public Domain)

For example, the researchers found that HHV-6A was capable of activating the genes for proteins such as PSEN1, APBB2, APPBP2, BACE1, and PICALM. These regulators were seen to be positively associated with the accumulation of amyloid precursor protein (APP), which is converted, in turn, to pathological forms of amyloid-beta in the brains of AD patients.

The investigators derived their samples from the Mount Sinai Brain Bank (MSBB) and focused on four prominent brain regions: the parahippocampal gyrus, the anterior prefrontal cortex, the inferior frontal gyrus, and the superior temporal gyrus. The Bank had between 107 and 213 brain samples for each region from both patient and control donors. These samples were then tested for 515 human viruses and reported that HHV-6A and HHV-7 were significantly abundant in AD brains compared to controls.

The researchers then validated these findings by looking for the same pattern in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex samples from the Mayo Temporal Cortex bank (which contained samples from people with AD, age-related cognitive defects, and PSP), the Memory and Aging Project and the Religious Orders Study.

These major consortium-led projects offered between 278 and 300 samples each from patients and controls. The team found that their analysis showed that the HHV-6A and HHV-7 counts were significantly higher in the AD samples compared to controls.

On the other hand, it was also found that these findings did not completely translate to the other disease states in the Mayo Brain Bank. The researchers reported that the AD brains exhibited more HHV-6A and HHV-7 than those with age-related decline. The PSP brains exhibited more HHV-6A when compared to the AD brains, but less HHV-7.

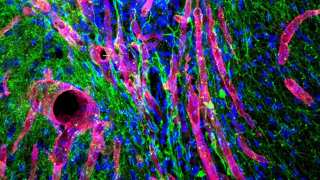

Mount Sinai researchers explain the purported associations between HHVs and AD. (Source: EurekAlert!)

The team, additionally, reported that human DNA significantly associated with the presence of these viruses, with the HHV-6A DNA, as well as characteristic HHV-6A and HHV-7 RNA fragments, was also associated with positive AD diagnoses, clinical signs and certain aspects of AD neuropathology.

Therefore, the group concluded that the viruses, particularly HHV-6A, might have the potential to drive AD progression in some cases. They attributed this to the phenomenon of the 'viral regulatory network,' in which viral genes interact with networks of human regulatory proteins in a complex process that ultimately results in the increased risk of pathological protein accumulations in the brain.

This may explain why the PSP samples (associated with the presence of neurofibrillary tangles or abnormal protein complexes that are present in AD, but in different brain regions compared to PSP) were found to have a possible association with HHV-6A, but the ‘age-related decline’ samples did not.

Though, these results emanate from just one study, and cannot be definitive proof of a causative link between AD and roseola-viruses. Further research, incorporating more or larger banks of AD brain samples or multi-omics data may be required to make solid conclusions.

Therefore, there is little reason for people affected by herpes-mediated conditions in childhood to worry just yet.

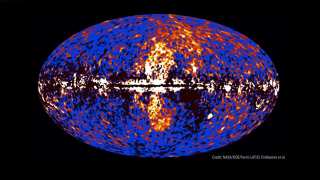

Top Image: A conceptual model of how HHV viruses may affect the brain in AD. (Source: Readhead et al., 2018)

References

Childhood Virus May Have a Role in Alzheimer’s Disease, 2018, smithsonian.com, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/childhood-virus-may-have-role-alzheimers-disease-180969432/ , (accessed 28 Jun. 18)

Unusually high levels of herpesviruses found in the Alzheimer's disease brain, 2018, EurekAlert, https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2018-06/tmsh-uhl061118.php , (accessed on 28 Jun. 18)

More evidence for controversial theory that herpesviruses play role in Alzheimer's disease, 2018, EurekAlert, https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2018-06/cp-mef061418.php , (accessed on 28 Jun. 18)

B. Readhead, et al. Multiscale Analysis of Independent Alzheimer’s Cohorts Finds Disruption of Molecular, Genetic, and Clinical Networks by Human Herpesvirus. Neuron.

No comment