Mosquitos are strongly associated with the spread of contagious viral conditions that can be fatal to humans. This is due to their habit of drinking blood from humans and other animal hosts, which increases the risk of viral transmission.

Therefore, many authorities and public health bodies have considered mosquito eradication as a solution to potential or actual epidemics. However, the population control for these insects is incredibly challenging, and the complete removal of an entire species can be considered as difficult.

A case study published in Biology Letters has reported that a recently-implemented strategy on Palmyra has resulted in the complete absence of one sub-species of mosquitos that is associated with the spread of diseases such as dengue and Zika.

However, the idea of replicating this success anywhere else could leave a bad taste in the mouths of ecologists and other experts.

Rats, Mosquitos and People on Palmyra

Palmyra is an atoll off the southern coast of Hawaii seized by the US army for its strategic value in World War II. As a result, this place has seen a steady level of human residence and visitation. Unfortunately, when the US occupied Palmyra, the country’s personnel inadvertently transplanted a colony of black rats (Rattus rattus) onto the atoll. The rats, in turn, supported a population of Aedes albopictus, the Asian tiger mosquito, another alien to Palmyra.

This mosquito type is a possible vector of many viral diseases, including chikungunya, yellow fever, dengue, Rift Valley fever, and Zika. It has the potential to spread disease, as the mosquito is unusually aggressive towards hosts and is active during the daytime, thus having plenty of access to its hosts.

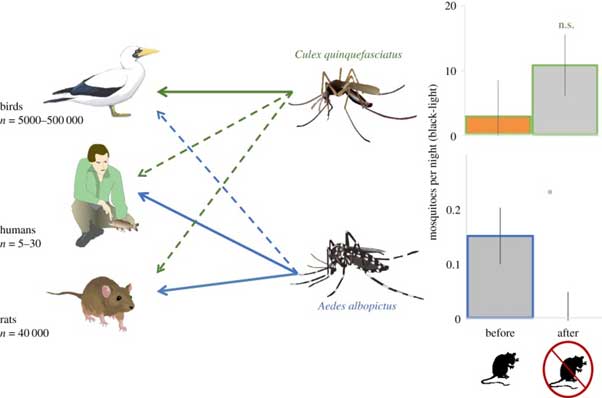

The Asian tiger mosquitos and black rats acted synergistically to exploit the native Palmyran environment. The mosquitos were only able to thrive by feeding on rat blood; furthermore, the coconut shells discarded by rats were ideal nursery spaces for their larvae. Therefore, the authorities eventually decided to eradicate the rats to compensate for this effect on the native ecology.

Rat-free Palmyra atoll. (Source: Rob Shallenberger)

In 2011, Palmyra experienced a widespread aerial drop of rodenticide that, effectively, killed off the black rat population. However, this left the Asian tiger mosquitos with nothing but humans to live on, or so it seemed.

Since the atoll’s treatment with rodenticide, reports of being bitten by this type of mosquito on Palmyra was in marked recession. The insect populations themselves, as estimated by trapping and counting, also seemed to be in sharp decline.

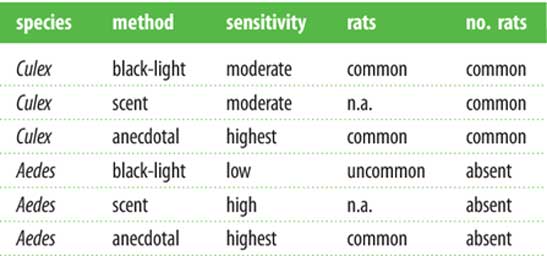

Eventually, a team of researchers from the University of California (Santa Barbara) conducted a more direct investigation of mosquito numbers using more sophisticated scent-based traps. The researchers also surveyed the people on Palmyra for reports of mosquito bites during the day. To their surprise, these reports were negligible.

The researchers repeated this protocol for two years with the same results, at which point WHO guidelines allowed them to conclude that the Asian tiger mosquitos had been eradicated.

A. albopictus numbers appeared to drop sharply following the extermination of R. rattus on Palmyra. (Source: Lafferty et al., 2018)

The Palmyra Stratagem: Is it Viable?

This appears to be very good news for other regions affected by aggressive mosquitos that are also viral vectors. But this concept can pose difficulties in the eradication of these insects elsewhere, and there are doubts if it can be replicated in other environments.

For example, it is apparent that humans were somehow inadequate as a food supply for the Asian tiger mosquitos in the absence of the black rats, and that the insects experienced a localized extinction as a result. However, this may be less applicable to situations in which human populations may be larger or denser compared to that on the atoll.

In addition, the UCSB researchers, who documented the results of their investigations in the journal Biology Letters, do not mention if any other mosquito-control measures (such as the protection of residential spaces from the insects) played a role in the extinction.

Table listing mosquito population, by species, before and after rat eradication. (Source: Lafferty, K.D. et al., 2018)

Furthermore, it may be irresponsible to propose this technique - a human-made secondary extinction - for the eradication of other mosquito populations.

The process could involve the identification of at least one other species as the primary target for the forced extinction. This may, in turn, lead to the detrimental knock-on effects for the ecological status of the area, and possibly impact the food-chain. In other words, such an experiment may lead to the end of the food supply for other animals, and, ultimately, for humans as well.

Finally, extinction-based policies for mosquito control may be ineffective if there are more than one sub-species of the insect (with their own ecological niches) in a given region. For example, Palmyra is also affected by a population of Culex quinquefasciatus, another type of mosquito also brought there by humans. These insects preferred to feed on seabirds, and, as a result, were unaffected by the rodent extirpation.

On the other hand, this study may have accidentally demonstrated that environments affected by non-native mosquitos with an equally alien preferred host animal may benefit from the eradication of both species.

This technique may need to be refined and applied with care if it is to be used as a solution for any area affected by mosquito-borne conditions. However, the risks involved in such a measure may be acceptable for some.

Top Image: Aedes albopictus, the Asian tiger mosquito (Source: James Gathany, USCDCP @ pixnio.com)

References

K. D. Lafferty, et al. (2018) Local extinction of the Asian tiger mosquito (<em>Aedes albopictus</em>) following rat eradication on Palmyra Atoll. Biology Letters. 14:(2).

J. C. Russell, et al. (2015) Tropical island conservation: rat eradication for species recovery. Biological Conservation. 185: pp.1-7.

M. L. Moir, et al. (2010) Current constraints and future directions in estimating coextinction. Conserv Biol. 24:(3). pp.682-690.

No comment