Discarded electronics are a potential hazard to the environment and to human living space. These products are still likely to end up in a landfill, in developed and developing countries, particularly as China does not need them anymore.

However, old gadgets are still sources of precious or valuable materials, particularly gold and copper. Therefore, extracting these metals and preparing them for use, may be a part of the industry in the future. Recent research has indeed indicated that this is possible.

In other words, our personal and home devices of the future could be using their predecessors rather than of ores torn out of the Earth.

Next-Generation Mining?

This concept is known as e-waste mining and involves processing electronics for the more valuable minerals and metals in them, which are then converted back into saleable forms (e.g., ingots).

A paper in the journal Environmental Science and Technology has investigated this idea in detail, and results have suggested that it may be at least as profitable as de novo mining.

The research was conducted by researchers at the Macquarie Graduate School of Management in Sydney, Australia and the State Key Joint Laboratory of Environment Simulation at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

The team evaluated the data on costs from eight e-waste processing concerns in China and compared them with corresponding information associated with more traditional forms of mining.

The researchers (Xianlai Zeng and Jinhui Li from Tsinghua and John Mathews from Macquarie) reported that their results indicated that the traditional mining was associated with a cost of 13% more than e-waste mining. These conclusions remained consistent even when they were corrected for potential extra steps in e-waste mining (e.g., the collection of electronics for processing, employee costs or custom-built fixtures and fittings). Therefore, the group of scientists concluded that e-waste mining could be profitable and feasible.

On the other hand, they suggested that those looking to get into such businesses may need specialist knowledge of metals and metal processing. In addition, e-waste mining concerns may need to be small-scale in the beginning.

E-Waste Mining in Practice

Some entrepreneurs have, in fact, implemented findings such as these and set up their own e-waste mining firms. Veena Sahajwalla, a professor at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), has set up her own ‘micro’-e-waste mining concern in Australia. This urban mining operation, which is also located at UNSW in Sydney, will be profitable in a "few years" in Professor Sahajwalla’s estimation.

Other e-waste mining projects, such as the EU’s ProSUM (Prospecting Secondary Raw Materials in the Urban Mine and Mining Wastes) initiative, are still in the experimental stages.

E-waste mining proponents such as Professor Sahajwalla maintain that this concept will bring many advantages to areas in which it is conducted. These include jobs and investment, and also it may help in tackling the sizeable backlog of e-waste that affects many countries, now that China’s anti-import policy is taking effect.

Much of this waste comes in the form of cathode-ray televisions, most of which are now firmly on the scrapheap in the wake of the flat screen revolution. However, smartphones are also often implicated in the accumulation of e-waste. Both product categories are ready sources of metals such as gold and copper.

Old cathode-ray tubes are still potentially useful to an e-waste miner. (Source: Rwanda Green Fund @ flickr)

On the other hand, e-waste mining does not address all the components of these electronics. They may also contain sizeable amounts of plastics, as well as glass, which may be discarded yet again in the process of mining.

Other forms of recycling, however, also encompass more elements of e-waste. They include recycling under the WEEE (waste electrical and electronic equipment) initiative. In countries like Ireland, this leads to the separation of metals, plastics and other materials in the course of e-waste processing. Therefore, all of these components stand a chance of being re-used. The WEEE system also accepts batteries, which contains valuable anode and cathode materials (e.g., lithium).

Old smartphones are replaced so often that they are a prime source of e-waste. (Source: Public Domain)

E-waste mining has a number of advantages. They include the potential for individual countries to control and exploit their e-waste independently while supplying jobs and economic benefits in the process.

On the other hand, these processes may produce more pollution, at least in the early stages.

In an age where we all routinely use and replace multiple forms of electronics, it remains worthy of, at least, considering, rather than drowning in discarded products that could, in fact, be out to use in new forms again.

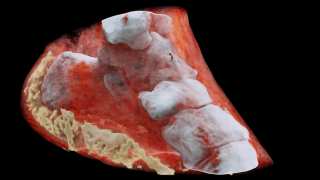

Top Image: E-waste is made of unwanted or broken electronics. (Source: Rwanda Green Fund @ flickr)

References

E-waste mining could be big business - and good for the planet., 2018, BBC News, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-44642176, (accessed 16 Jul. 2018)

Recyclers conquer Ireland’s electronic waste mountain, 2018, Irish Times, https://www.irishtimes.com/business/technology/recyclers-conquer-ireland..., (accessed on 16 Jul. 2018)

X. Zeng, et al. (2018) Urban Mining of E-Waste is Becoming More Cost-Effective Than Virgin Mining. Environmental Science & Technology. 52:(8). pp.4835-4841.

No comment