Depression is an often-chronic mental health condition long acknowledged and recognized by official psychiatric categorical systems such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-5 (DSM-5). However, the research into its risks, development, and treatment remains hampered by the lack of diagnostic markers for the condition. In other words, neuroscience has mostly failed to pinpoint characteristic variations in brain activity that can be detected or monitored using non-invasive imaging techniques such as MRI.

The identification of such depression-specific changes could be a significant asset in terms of the condition’s management. In addition, this discovery may help stop cases of depression being misdiagnosed as other disorders with overlapping symptoms (e.g., bipolar or seasonal affective disorders).

A new paper in the journal Nature may have finally unearthed the first signs of a connection between the different, relevant brain areas associated with depression.

Reward, Its Memory and Depression

This article, authored by Scott Thompson and his team from the departments of physiology, anatomy & neurobiology, pharmacology, and psychiatry at the University of Maryland’s (Baltimore) School of Medicine, has described the identification of a neural connection between the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and hippocampus (Hc) of the brain.

This conduit, made of synapses between the neurons running between these two structures, was found to influence reward-anticipation in experimental mice. The Thompson team chose to focus on this connection from the hippocampus (the brain’s ‘memory center’) to the outer layer of the NAc (the brain’s ‘reward-processing’ center) as it was likely to influence the same.

The inability to derive emotional ‘highs’ from typical reward-associated stimuli (e.g., activities that the patient could ideally enjoy or take pleasure in), known as anhedonia, is a central symptom of depression.

However, researchers have not been able to find specific brain activity associated with anhedonia. Nevertheless, the prevailing theory is that should this activity exist it is particularly low in people with depression. Conversely, it may be abnormally high in those with other disorders (e.g., addictions or substance abuse disorders).

Therefore, Thompson et al. pinpointed this Hc-NAc connection and its variability (or plasticity) in a mouse model of depression.

Creating Happy Memories for Mice

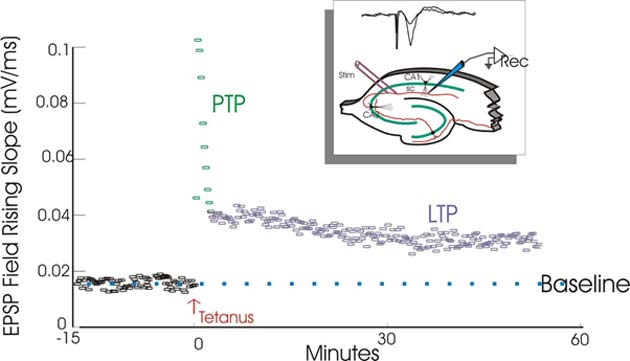

The researchers did this by engineering mice with an optically-activated (or active when exposed to light) protein that could stimulate neurons in this Hc-NAc pathway. The protein enhanced the long-term potentiation (LTP) of the neural synapses, which is an important component of brain activity stemming from regions such as the Hc. These activated neurons resulted in the creation of an artificial, reward-linked memory that was also associated with a specific area in the murine enclosure.

As a result, four-second bursts of light exposure in the proteins stimulated a mouse to go to this part of a cage. This effect, known as place-preference, is strongly associated with reward-identification in animal models. For example, a mouse might repeatedly return to a specific location in which they had previously had a positive social experience with a second mouse, as if in the hopes of meeting the same animal there again.

Long-term potentiation has many functions in the brain, including the maintenance of a neurological response to a high-frequency (or tetanic) source of stimulation. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Therefore, ‘normal’ mice with these proteins exhibited the requisite place-preference in response to the light-exposure procedure, as these rodents ‘remembered’ gaining some kind of reward as a result.

Mice with experimentally-induced depression (through the induction of chronic stress), however, displayed reduced tendencies to go to the designated area in the course of the same procedure in response to controls. This effect was at least partially reversed when these mice were treated with antidepressants.

Moreover, the researchers found that turning the Hc-NAc pathway off using different light-activated proteins resulted in reduced ‘natural’ place-preference behavior. For example, the normal mice in whom these proteins were activated exhibited no will to return to a spot in which they had previously encountered a second mouse.

In addition, the researchers reported that the neurons driving the relevant LTP in this study were not associated with the neurotransmitter dopamine, the brain’s classical ‘reward chemical.’ Therefore, anhedonia may be related to the inability to retain or maintain the synaptic activity underpinning the links between memory and reward-anticipation in the brain.

Therefore, this experiment may have provided evidence that the neural pathway in the brain may be specifically associated with anhedonia in depression.

On the other hand, the results of this animal study should be validated and replicated rigorously before anything can be confirmed about analogous brain activity influencing anhedonia in human patients.

Nevertheless, it may turn out to be a useful first step in the improved imaging of, and thus, diagnosis and treatment of depression.

Top Image: Could impaired or damaged synapses in the brain be specifically related to depression? (Source: Joe Flintham/Flickr)

No comment