Don't you wish, sometimes, that you could get rid of the urge to binge-eat and indulge in sweet treats? Even if you agree, unfortunately, the brain does not work in that manner.

In fact, the scientific community has asserted that overeating can be considered a neurological disorder. In addition, the enjoyment derived from eating pleasant-tasting foods is almost always entangled in a web of emotional and psychological responses of various kinds.

These reasons could offer an explanation as to why "eating" conditions are difficult to treat.

A team of researchers from Columbia University’s Zuckerman Institute has investigated some facets, of this phenomenon, in an animal study. The basis for their experiments was a colony of mice in which the specific neural tissue and connections associated with different tastes in the amygdala could be switched off.

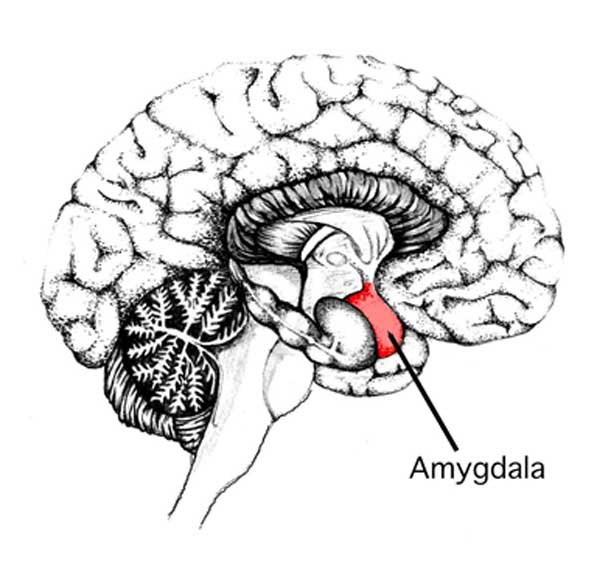

Previous work had shown that the taste center in the brain was connected to specific termini in the amygdala. This was a groundbreaking find, as the amygdala is known to be associated with emotional responses to stimuli, and not taste processing.

Illustration pointing to the amygdala of the brain. Certain regions of this part are believed to be responsible for tastes such as sweet and bitter. (Source: Wikipedia)

Furthermore, the group also reported that the neurons in the taste center responsible for sweet and bitter tastes had their own distinct destinations in the amygdala. This discovery could suggest that different tastes are, or become, related to the various emotional states.

Tasting with Your Brain

Normally, these targets in the amygdala are quiescent until they are activated by their respective ‘taste’ connections from the cortex of the brain (which, in turn, is connected to nerves running from the tongue).

However, the Zuckermann Institute researchers found a way to control the sensations, externally, in test mice. When they switched on the ‘sweet-taste’ tissue in the amygdala, they found that the mice reacted to plain water with the same amount of enthusiasm that they normally reserved for sugar.

Another type of neurological switch could cause the mice to perceive sweet tastes as bitter. This is the reason why the mice reacted to sugar in the same way as they did a sour-tasting analog or vice versa.

Mice like treats for reasons similar to that of humans. (Source: Meditations @ pixabay.com)

Turning Off the Need for Sweets

These results required that the scientists manipulated the connections from the taste cortex ends as well as those in the amygdala. When they left the amygdala-ends "on," it was that the mice appeared to recognize different tastes as normal.

However, the team also failed to exhibit the normal behavioral responses to experiencing either sweet or sour. The researchers likened these responses to a sudden absence of the impulse to abuse food in a patient who would normally be inclined to binge-eat when presented with their favorite treats.

Therefore, this research may have important implications for the treatment of various addictions and, possibly, their underlying psychological roots. However, such work would require much more extensive validation, elaboration, and up-scaling of the Zuckermann team’s project.

In more immediate terms, this research is an important piece of evidence for the links between foodstuffs, especially different tasting ones, and brain activity beyond the taste cortex.

For example, it now appears that this activity is much more pervasive and prevalent than once thought. On the other hand, it also indicates the different components (such as the connections that determine the enjoyment of different tastes) that can be isolated with increasing precision.

Brain Switches: The Future of Addiction Treatment?

All in all, this project is a potentially vital component of next-generation neuroscience research and understanding. There are also numerous future directions for this branch of study. For instance, the long-term effects of the taste cortex/amygdala connectivity could be elucidated.

This area of the brain could also be implicated in certain conditions; therefore, its study could lead to improved treatments.

In the meantime, it looks like we will have to continue relying on our willpower to keep from eating all the chocolate that's left in the fridge!

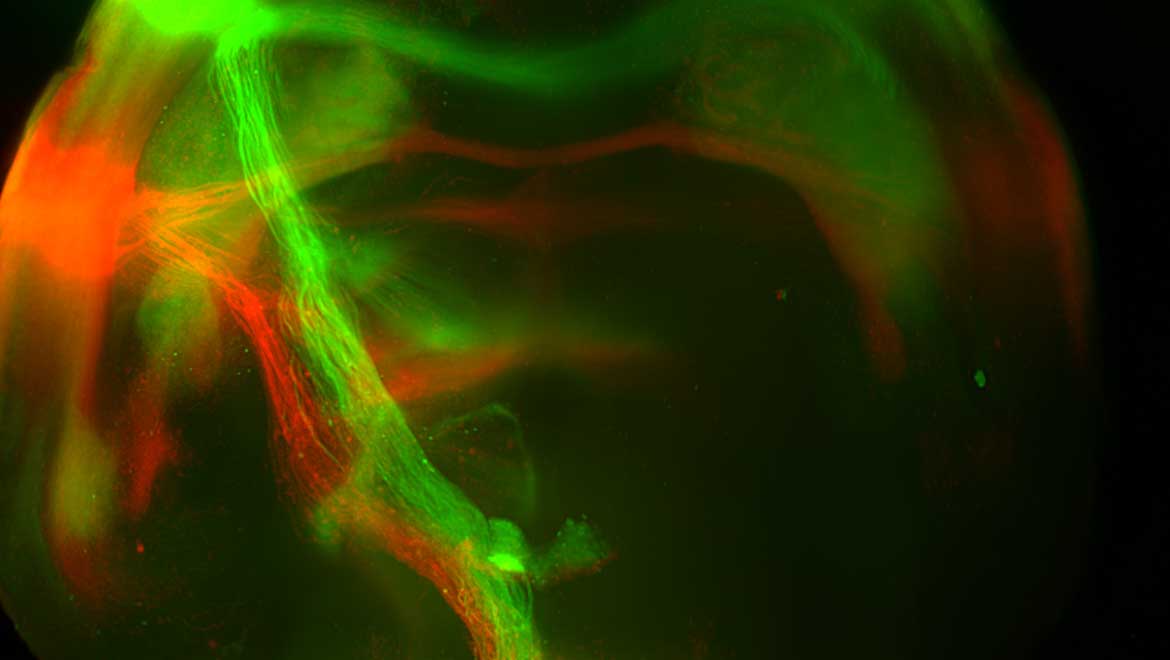

Top Image: Taste cortex neural connections (sweet=green and bitter=red) find their targets in a mouse-brain amygdala. (Source: Li Wang/Zuker Lab/Columbia's Zuckerman Institute)

No comment