The human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) is associated with infection in 37 million people worldwide. Its contraction can cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), which may result in significant losses of life quality and mortality in many cases. An HIV-positive status is an insidious condition for this reason, and for its historical resistance to medical treatment.

However, it seems that the research behind these therapies may finally be getting the upper hand on the exceptionally robust retrovirus.

A few years ago, clinicians reported the first case of HIV-1 clearance from the blood of one individual (the “Berlin patient”). This may sound insignificant but is much less so against the millions worldwide who are never likely to exhibit the same medical profile.

The report, therefore, was particularly ground-breaking as it represented the possibility of a future in which patients will not have to undergo antiretroviral therapy for life, as an estimated 21 million people do at present.

A New Way to Eradicate HIV?

This trial involved steps in which the subject was obliged to undergo full-body radiation treatment, in order to suppress the immune system that HIV-1 had hijacked and turned against him. The patient also received two grafts of stem cells from a donor with two copies of the Δ32/Δ32 mutation in the CCR5 gene. This mutation could confer resistance to HIV-1. Therefore, the rationale was that these grafts (allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantations or allo-HSCTs) would multiply and differentiate into a whole new, HIV-1-beating immune system. For all intents and purposes, this worked.

Then again, there were also sizeable drawbacks to the protocol used in the case of the "Berlin patient." The radiation therapy and allo-HSCTs resulted in severe adverse effects for the subject – however, the former did also address the case of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with which the individual was also affected. Nevertheless, the new technique resulted in a favorable effect: the patient was reported clear of HIV-1 without antiretroviral therapy for 20 months’ worth of follow-up.

This lack of viremia (or viral load in the blood) was quantified using techniques such as DNA- and RNA-PCR assays, biopsies, and immunological studies. They showed that viral RNA was “undetectable” for up to 20 days post-allo-HSCT and that the patient did not express T-cells (a type of immune cell) with anti-HIV1 receptors, or anti-HIV1 antibodies. The patient’s stem cells also became chimeric or changed from a ‘normal’ CCR5 genotype to one with Δ32/Δ32 mutations.

Therefore, medical research groups bided their time to find another suitable patient in whom the protocol could be tested again.

Eventually, a team from several UK institutions identified one patient at the University College London Hospital. This individual had the same strain of HIV-1 as the Berlin subject and was similarly in ill health. He also had Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which could be treated with allo-HSCTs. However, in this case, the team decided to take the risky step of omitting the full-body radiation component of the treatment.

This group, led by Eduardo Olavarria of Imperial College London, reported that the side-effects, which resulted from this tweak in the process, were less severe than those documented in the Berlin patient’s case. The “London patient” had mild host/graft gut disease, but not much beyond that.

The team also reported that this procedure resulted in remission from HIV-1 over 18 months, with “less than 1 copy [of HIV-1 RNA] per milliliter [as a result of PCR] along with undetectable HIV-1 DNA in peripheral CD4 T lymphocytes.” Therefore, the patient may have what is known as ‘functional resistance’ to HIV-1.

These findings have been published as a case report in the journal, Nature.

Is This the End of HIV? Probably Not

This report’s authors have recommended that the research community and public do not get ahead of themselves in interpreting the case. They assert that 18 months is still too soon to make a claim that the patient will experience outcomes such as long-term clearance of HIV-1 in his blood.

However, unfortunately, this has not stopped some outlets from using rather irresponsible wording, including the phrase “reported cured,” in their articles on the subject.

The two cases highlight some unfortunate drawbacks of next-generation HIV treatment:

From an ethical standpoint, both patients were only eligible for such treatment as they happened to have additional conditions (Hodgkin’s or AML) that could also be addressed using allo-HSCT. Other patients may not have these (dubious) privileges.

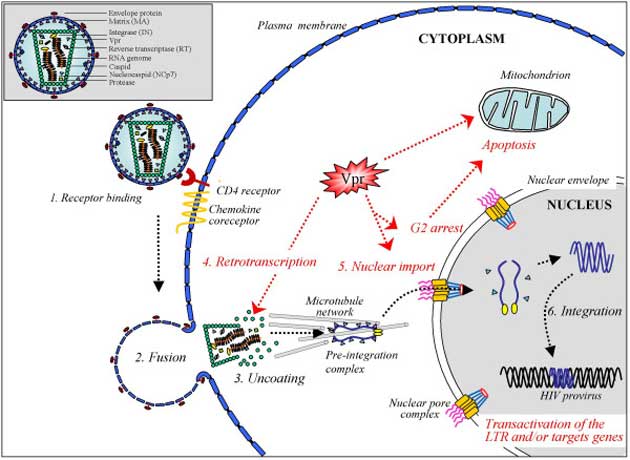

Furthermore, their apparent remissions have only been possible due to the CCR5-mutation-susceptible (or CCR5-tropic) nature of the HIV-1 strains involved. Had another strain, such as the CXCR4-tropic variant of HIV-1, been involved, the treatment would have been incompatible with the virus and how it affects the immune system.

Furthermore, this differential susceptibility is another potential "Achille’s heel" of the new, emerging protocol in HIV treatment.

Some rare strains of the virus can be both CCR5- and CXCR4-tropic, as explicated in the case of the “Essen patient.” This individual was involved in the only CCR5∆32/∆32 allo-HSCT trial that existed prior to the one in Berlin. It failed when the viral loads assessed started to express CXCR4-tropism and experienced a resurgence before the graft could be implanted.

A schematic outlining how the HIV-1 virus infects a cell. The ‘chemokine receptor’ may be expressed by CCR5 or CRCX4. (Source: Le Rouzic et al, 2005, Retrovirology)

This, again, highlights yet another pitfall in the “London” and “Berlin” processes: any pre-existing antiretroviral therapy has to be discontinued for about a week prior to an initial allo-HSCT. That period presents the HIV particles with an excellent chance to express an atypical form of resistance or immune-cell infection, thus rendering the patient ineligible for the procedure.

It follows that HIV-1, which has shown itself to be extremely versatile and resourceful in the past, could somehow acquire, develop or otherwise evolve a new form of resistance with which to circumvent the effects of allo-HSCT in any case.

Nevertheless, the new, allo-HSCT-based procedure appears to be the safest, most tolerable and, above all, the most effective method of significant HIV-1 viremia reduction in medical history.

It is to be hoped that it can be refined and adapted to treat patients both with and without CCR5-tropic HIV-1 variants - as well as more cost-effective for the average patient - in the future.

Top Image: An artistic representation of an HIV virus particle. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

No comment