Recently, the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) had a bit of a mystery to solve. Its deep-space telescope, Kepler, had gone to sleep unexpectedly, and its operators could not get it to wake up or respond again. This unscheduled move by the craft was reported by NASA on October 19, 2018. A few days later, the space research authority returned to the press with the news that Kepler had run out of fuel, and would be sending no new images as of October 31, 2018.

As if this was not enough misfortune for NASA, its scientists have just learned that another revolutionary exploratory vehicle, Dawn, is also out of fuel and will shut down forever. In this case, this news, however sad for the team, was not as surprising as the Kepler malfunction.

Dawn was expected to run only for 8 years, but even then it persisted into late-2018 with its missions, which was to approach and orbit the best candidates for the study of the early solar system.

Two of these cosmic objects were Vesta and Ceres, virtually planetoid asteroids that are known to exist in the system’s main asteroid belt. This belt may contain the best examples of materials ‘leftover’ from the formation of the solar system, at a time when it was a little more than a colossal disc of cosmic dust floating in space. Both these asteroids are probably the oldest solid bodies left in the asteroid belt, as it is apparent from the vast size they have retained.

Therefore, the team had indicated that a valuable source of the radiation, elements and other factors may be determined from the formation of the solar system.

The Dawn of Ion Propulsion

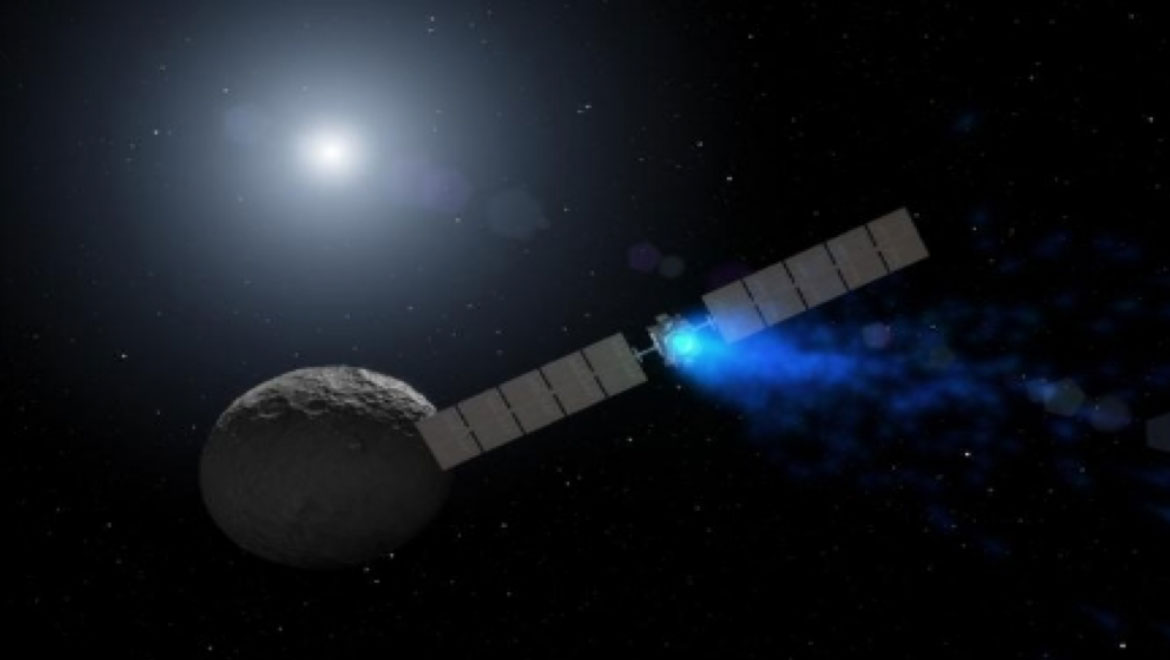

The team launched Dawn in 2007 to journey towards an orbit near both Vesta and Ceres. Dawn was a state-of-the-art probe that used hydrazine as a fuel to propel itself towards and around the two bodies. This was done using a form of flight-using ion propulsion.

Sound familiar? It should - ion propulsion was originally conceived as a method of travel in the Star Trek fictional universe!

The Dawn team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) aimed to make this technique a reality. They enabled the space probe to orient itself in space, to target either Vesta or Ceres and break out of their gravities at need.

Therefore, it was observed that Dawn was capable of escaping an orbit that it had joined in order to study the body to which it was applied. This property enabled it to apply its instruments to both Ceres and Vesta in detail.

These scientific tools were a gravity- and mass-measuring audio instrument, a visible-to-infrared light spectrometer, the GRaND gamma-ray, and neutron detector and its camera, which captured images of the asteroids in color and black and white.

An overview of the Dawn mission. (Source: NASA-JPL/YouTube)

These instruments returned impressive readings and images of the two ancient bodies.

Dawn was able to verify that Vesta was a more or less simple asteroid that did not look dissimilar from our moon. Ceres, on the other hand, was a larger, more complex body with ‘bright spots’ indicating the presence of various elements and compounds. Some of these, including the highly atypical sodium carbonate, may indicate a history of water on Ceres at one time or another. Sodium carbonate was not readily found in the solar system since it was only associated with moons like Enceladus and water bodies on Earth.

Besides this, Dawn also exhibited the ability to conserve its fuel better than the JPL team had expected, adding three years to its mission.

The depth and breadth of this telemetry have vastly improved our understanding of Vesta and Ceres, and of the solar system’s history in general. The two bodies are now classified as dwarf planets, and maybe the focus of more study even after Dawn stops sending data.

The probe is now officially considered dead and will remain in orbit around Ceres for 20 to 50 years. Therefore, Dawn will spend the foreseeable future, as it spent its active life, except it will never hop out of orbit back to Vesta again. The team at NASA will be sad to say goodbye, but they will also be proud of its unprecedented achievements.

What About Kepler?

As for Kepler, it too will be celebrated in the astronomical and astrophysical community for some time to come. Its trajectory took this space probe in the approximate opposite direction to Dawn, aiming to orbit the sun as it imaged worlds far and wide outside the solar system. Findings have revealed that there are planets out there that do not conform to those in our own system - some are possible Earth-like planets (although their size may not equal that of our planets), whereas others are ‘super-Jupiters’ that could swallow nearly every planet nearer to our own.

An artistic impression of Kepler-186f, one of the first ‘super-Earths’ imaged by the Kepler deep-space telescope. (Source: NASA/JPL)

Kepler will soon stop spotting these exoplanets for us for good and drift in space having used up its fuel. In the meantime, it will send the last data it had gathered, which concern about 2,900 possible exoplanets for verification once this information reaches Earth.

However, like Dawn, Kepler is not likely to be forgotten soon.

Top Image: An artistic impression of Dawn propelling itself towards Ceres. (Source: NASA/JPL)

No comment