It is in the human interest to be able to predict when natural disasters of various types are going to happen. This becomes particularly important when homes are in the paths of storms or could be affected by flooding because of them.

Accordingly, meteorological scientists have developed increasingly effective prediction models that can help forecast hurricanes, for example. These storms occur, often at least once, at the rough start of autumn, and affect movement and industry in the Atlantic or near-Atlantic area.

Recent research indicates that a certain species of small bird may have outdone these models all by themselves.

Migrating through the Storms

The birds, who are often songbirds such as thrushes or warblers, live in more northerly areas for some of the year, fly south for the rest of it, then migrate back where they had been. Some of these birds have to traverse the entire North American continent in order to do so. They have done so from about August to October every year for decades on end.

However, it is also known that these birds could move around during the major hurricanes of the past. Therefore, they may be extremely vulnerable to hurricanes that cross their migratory paths. It is thought that this risk is a prime driver of mortality in these birds, who may be blown into the ocean or otherwise be fatally injured while on the wing in a migratory flock.

Some birds may survive being knocked about by fierce winds but they probably will never find their way back to the flight-path or their original, seasonal homes. Therefore, it makes sense that these birds may have evolved to assess the risk of hurricanes before they even take off.

A study conducted in 2018 suggests that not only have they achieved this, but they can also tell how severe the upcoming hurricane season is going to be. This research indicates that a particular species of these migratory birds even alters their breeding and other behaviors accordingly. Some variables associated with this activity even correlated strongly with the hurricane severity index for the same year.

How Humans Predict Hurricanes

This hurricane index is known as the Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index. It is calculated by taking the length and strength of all hurricane activity, in a given season, into account. These variables are thought to be influenced, in turn, by the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation, as well as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). They are prominent, significant climatological phenomena that are thought to contribute to stormy weather in the Atlantic basin region. Therefore, advance storm warnings by bodies such as Colorado State University (CSU) and NOAA, as well as the Tropical Storm Risk (TSR) forecast, are based on the ACE and released in August.

The ACE was also used in this study, which analyzed the breeding and pre-migration behaviors of the veery (Catharus fuscescens), a type of thrush that nests in the state of Delaware before migrating all the way to the Amazonian basin for the winter. This bird has been observed to be a single-brood species. In other words, they raise only one clutch of eggs to chicks in any given season. In addition, they nest in order to raise this brood. However, interestingly, this nesting behavior has been observed to change in accordance with the oncoming hurricanes and their severity.

In other words, the birds will nest, breed, incubate eggs, and hatch them before seasons for which the subsequent hurricanes have turned out to be more severe. This is apparently done in order for them to be ready to migrate earlier in the year and thus, skip the worst of the storms.

Veeries: Forecasting Hurricanes For Decades

A study conducted by Christopher Heckscher and his team of technicians at the Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Delaware State University, studied this behavior in detail for an entire season while the birds nested in White Clay Creek State Park in Delaware.

The team observed the birds for 4 to 7 hours, 4 to 6 days a week from the first week in May until the third week of July (when veeries stop breeding) for 19 years until 2016.

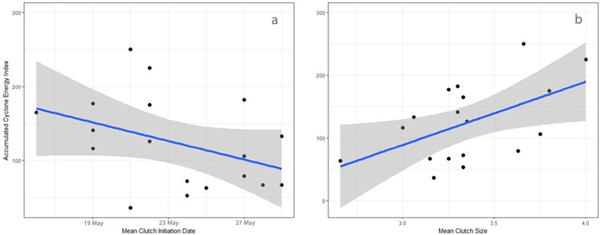

Following this, Heckscher analyzed this data using the Spearman technique for statistical relationships. He then reported that the average date of egg-laying in veery females had a strong correlation (or r2 value of -0.55) with the actual number of severe hurricanes that year. In addition, the researcher found that the average size of each clutch was also positively correlated (r2 = 0.52) with the number of these hurricanes. These factors were strongly correlated with ACE (r2 values of -0.36 and -0.45 respectively).

Therefore, it seemed that females were more disposed to start breeding earlier in years of high hurricanes and also laid larger clutches per nest.

These plots illustrate the relationships between ACE and the Delaware veery nesting patterns between 1998 and 2016 (one year’s data was lost). (Source: C. M. Heckscher., 2018)

This clutch size value was calculated by counting the number of nests and the number of eggs in them. Veeries are inured to losing at least one nest to predators or other factors, and they will build another with a subsequent clutch in it. These clutches of eggs are typically relatively low in number. However, it appears that this number has increased in years of bad hurricanes, in order to give the best chance of hatching live chicks quickly. This behavior is now apparently corroborated by the new scientific data.

In addition, the correlations were seen to be at least as strong compared to those between the institutional August forecasts and the ACE (which were reported to be r2 = 0.45 or less).

In addition, breeding initiation and average clutch sizes were not found to be statistically significant (r2 = -0.07, with a p-value of 0.77). Therefore, it appeared that hurricane severity, as foreseen by the birds, was more likely to be the main predictor of these variables.

Heckscher also reported that, for the years when this date preceded the 23rd of May, the number of major hurricanes was three or more, while when the initiation date was after this date, the number was two hurricanes at the most. This association was verified with a chi-squared value of 4.8 and a p-value of 0.03.

Therefore, it now appears that these birds can predict severe hurricane seasons at least as well as humans can.

On the other hand, the time-frame of the study represents a small sample size compared to the amount of storm data available. Nevertheless, this is an interesting indication of how weather patterns are perceived and adapted to in nature.

The study also suggested that the veeries take other factors, such as the rainfall during their stay in the Amazon, into account when preparing for the hurricanes of the subsequent studies.

Also, research like this may improve our own ability to predict serious weather events in the future.

Top Image: The veery, a small migratory thrush on which this research is based. (Source: Kelly Colgan Azar/Flickr)

References

This Bird Predicts Hurricanes Better Than Meteorologists, 2018, Nature Blog, https://blog.nature.org/science/2018/09/26/this-bird-predicts-hurricanes-better-than-meteorologists/, (accessed 2 Oct 2018)

C. M. Heckscher. (2018), A Nearctic-Neotropical Migratory Songbird’s Nesting Phenology and Clutch Size are Predictors of Accumulated Cyclone Energy, Scientific Reports. 8:(1), pp.9899.

J. B. Elsner, et al. (2006), Prediction Models for Annual U.S. Hurricane Counts. Journal of Climate, 19:(12), pp.2935-2952.

C. M. Heckscher, et al. (2011) Veery (Catharus fuscescens) Wintering Locations, Migratory Connectivity, and a Revision of Its Winter Range using Geolocator Technology, The Auk, 128:(3), pp.531-542.

C. M. Heckscher, et al. (2017) Reproductive outcomes determine the timing of arrival and settlement of a single-brooded Nearctic–Neotropical migrant songbird (Catharus fuscescens) in South America, The Auk, 134:(4), pp.842-856.

No comment